This is a review of an exhibition I attended – Balenciaga: Spanish Master – at the Queen Sofia Spanish Institute in New York during a recent trip. I have never written about Balenciaga and so have gone off on several tangents of interest to me – if not you as readers. The thoughts I present are my own and open to discussion. I love an exhibition as much as anyone and my thoughts are based upon my own expectations and observations.

The building in which the Spanish Institute resides had once been, I suppose, a private residence, so due to the floor plan the works are split over two levels and in three completely unattached rooms. Here Hamish Bowles – American Vogue’s European Editor at Large and the exhibition curator – has separated the clothes thus; into those inspired by the religious and monastic and those influenced by the flamenco and the bull-ring. The exhibition checklist further breaks these down into Royal Court, Religious Life, Spanish Art, Regional Dress, Dance and the Bullfight. The third room shows no clothes, but offers supporting design ephemera, collection footage, and some glorious original (I assume) mirrors from the Paris maison. Obviously Mr. Bowles had to make the most of the environment he was given and while generally successful, the separation does give the experience an uneven feeling. It will be interesting to see how his bigger Balenciaga exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco fares this (northern) spring.

In the exhibition brochure, Mr Bowles quotes Diana Vreeland as noting that Balenciaga “remained forever a Spaniard… his inspiration came from the bullrings, the flamenco dancers, the fisherman in their boots and loose blouses, the glories of the Church and the cool of the cloisters and monasteries. He took their colors, their cuts, then festooned them to his own tastes…” Here it appears Mr. Bowles has chosen to edit Mrs. Vreelend’s quote for the sake of the exhibition. In Lesley Ellis Miller’s book Balenciaga this quote reads differently and takes on a slightly patronising tone in its entirety. “…he took these models and colors and, adapting them to his own tastes, literally dressed those who cared about such things for thirty years.” I doubt whether Mrs. Vreeland meant to sound as negative as my interpretation of her quote, but nevertheless hers more appropriately reflects my own experience of the exhibition, as I am never one to get excited about a themed collection, let alone a themed exhibition. Either way, the influence of the Spanish experience upon Balenciaga provides the underlying focus of the exhibition.

It is perhaps generally ignored – or maybe just overlooked – that Balenciaga had already been a successful designer is Spain for twenty years before the Spanish civil war forced him to flee to Paris. The influence of his homeland continued throughout his career although Mr. Bowles argues it became less “overt” and became more “oblique, but no less powerful.” In her review of the exhibition, Cathy Horyn of the New York Times also follows this train of thought and notes that as an older Spaniard working in Paris, a combination of maturity – he was already 42 when he first showed in Paris – and distance amounted to “incredible refinement,” in his design choices. “The influence of regional dress is there in his clothes – and it isn’t.” I like this idea, as it explains that he managed to produce clothes that aren’t costume, but contain the very essence of their inspiration.

As a sidenote, I also attended the Initiatives in Art and Culture Fashion Conference – Vintage: Value, Values, and Enduring Design; at which Mr. Bowles spoke about his extensive research into the work of Balenciaga under the title of Enduring Design. Talking about the exhibition, it was of course Mr Bowles’ job to point out the Spanish influences and he did so with gusto. His 45 minute timeslot during the conference extended into 75 presenting so many examples that it prompted one guest to ask if they were in fact confirmed as direct influences by the Master himself. Mr Bowles had to admit that he could not say for certain that they were direct references, but the connections where plausible. He did share several interesting stories about putting together the exhibition – one of realising that a hat from his own collection was coincidentally designed for one of the pieces in the show and the fact that the interlining of the 1939 “Infanta” dress from the Balenciaga archive was determined by pencil marks showing fitting notations to be the original toile of the style.

Spain was of course in Balenciaga’s blood, providing him with a huge inherent repertoire of exotic influences. What struck me however, was the general lack of joy in the clothes and their presentation. I have never seen Balenciaga as a particularly joyous designer, but in many instances even the technical aspects of his work can’t override a certain dourness. This is not to say that all on display is dull, but the general gloominess of the spaces and the predominance of black clothes certainly didn’t help. There are several pretty items, but generally the exhibition lacked pizzazz – enough anyway to sell the idea that there is as at least something bubbling below the surface if not popping in your face. It was the same feeling I had reading the book Balenciaga and His Legacy: Haute Couture from the Texas Fashion Collection by Myra Walker. Never a sadder bunch of designer clothes had I ever seen published. I have since noticed that many garments from the exhibition are on loan from the same collection.

I sometimes have the feeling that when Balenciaga is presented to an audience they are expected to “get” the relevance of his work. I think the general public and even lovers of fashion and its charms don’t always appreciate the technique that makes his work worthy of display and research. And they aren’t helped out here as the somewhat contrived mystique of the house of Balenciaga is perpetuated by Mr. Bowles himself. Plastered over one wall in the “salon” room are quotes boasting of his technical mastery and obsession with detail with the use of phrases like “his hypercritical eye” and “impatiently taking the scissors from the fitter and slashing the dress up the front in the most terrifying manner.” The silliest one comes from Gloria Guinness who claims that “working on the cut of a sleeve, he would neglect all else and go without food or sleep for days and nights.” I certainly appreciate the possibility that this is a true statement, but these quotes appear to be presented as examples of his genius and not reasons for it. Where are the descriptions of the subtle methods by which he could reduce darting, yet still manipulate fabric to hug the figure seductively, or how he could create volume without the underlying bulk of a similar Dior gown?

Cristobal Balenciaga

One reason for this neglectful state of affairs is perhaps the fact that Balenciaga never gave an interview during his career and only gave one three years after his retirement to English fashion journalist Prudence Glynn in 1971. He justified his reticence by claiming he found it impossible to explain how he worked and that inevitably any discussion of his process would lead to possible comparisons with other designers. Chanel had no such issues and cultivated her own mystique of hard work and obsession with detail and construction. There is a story of her refitting a jacket sleeve seventeen times before she was happy with its hang. I have always seen this however as a sign of slight ineptitude rather than an obsession with construction. It is people who don’t understand the process who are impressed by such statements and Chanel – a genius of marketing – knew this as well as anyone. Even she recognised Balenciaga’s true talent and stated “Balenciaga alone is a couturier in the truest sense of the word. The others are simply fashion designers.” Dior, in his book, Dior by Dior, charmingly explained every aspect of his creative process, but Dior was a stylist and not a hands-on technician. He also wrote flatteringly of Balenciaga; “Haute couture is like an orchestra, whose conductor is Balenciaga. We other couturiers are the musicians and we follow the directions he gives.”While these flattering quotes from his peers certainly provided good press, Balenciaga didn’t need the publicity as his collections were commercially successful from the outset. His decision not to sell himself as a brand was further maintained by several other factors. The fact that he chose to show his collections a month after the other Paris designers; that his collections evolved season by season rather than being revolutionary and that he didn’t give his collections titles or individual garments charming names all meant that the fashion press took control of that part of the job for him. As already mentioned, the mystique that developed around the house and the designer himself came from impressions gleaned from clients who rarely had any contact with him and editors who only had limited access and possibly understanding of his creative process – as well as magazines to sell. It was one-time editor of American Vogue, Bettina Ballard, who wrote dramatically of him slashing the garment during a fitting – even though it is a rather standard technique for anyone who drapes on the model.

I would argue that because of this disconnection between the couturier and the press, so much of what Balenciaga created throughout his lifetime became public property upon its unveiling and so was prone to uneducated or lazy interpretation; with his “Spanishness” providing the most obvious point of reference. Despite this, the visual language he decreed was so modern and appropriate to the times in which it was created it is hard to separate it from what clothing has since become. It is perhaps sometimes out of “fashion” but it is never out of place. This is the reason I believe Balenciaga should be hailed a genius. The fact that we can look at his clothes and take them for granted – be almost unimpressed by them. This goes some way in explaining why I think I was unimpressed with Mr. Bowles’ curation.

In any exhibition of his work, I believe it is up to the curator to find a way for us to be dazzled by the work of Balenciaga. Using the theme of the influence of Spain on his work should have provided us with an experience similar to the same inherent connection between Christian Lacroix and the Camargue or Vivienne Westwood and the history of Britain where a sense of passion and joy is never far from the equation. The exhibition had a solemnity which I suppose was meant to represent reverence, but what Mr Bowles needed to create was an atmosphere in which black meant life, ruffles inspired you to dance, lace spoke of both sex and innocence and where luxury was a promise, not a dream. And to this end, I think he failed.

To make vintage fashion relevant to a modern audience, a certain sense of spectacle has to come into play. It is not simply enough to say that this jacket looks like a suit of lights as worn by a matador, or that the carnation print of a dress represents the national flower of Spain. It has to be so much more than that. I felt the exhibition lacked the context in which the clothing originally appeared and the impression it would have made on the women of the day.

Perhaps I would have gone back for a second look and been more forgiving had I not had to pay $15 to see the show. I did however return several times to Barneys where I had floors of fabulous clothes at my fingertips; including Balenciaga Edition. This secondary line recreates – indeed replicates – garments from the 600 piece Balenciaga archive in the same fabrics and using precisely the construction techniques used in the original couture pieces. Rather than stand behind a glass wall, these clothes could be felt and handled and the secrets of their construction revealed to me without so much as a peep from the sales associates. The context of modern clothing is provided by the store itself, the fashion shows, the myriad ways in which the media presents the garments for public consumption, magazines, television, the internet and the like. Competing against this “free” context, the fashion exhibition has to create its own. Mr Bowles used coloured screens and some photomurals to help in this regard. The church mural was is particularly striking and worked in setting the appropriate scene as well as opening up the visual space within the room. The smaller ones showing art works, matadors, a bullfight and such are also effective, but it was not enough.

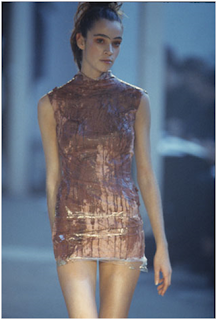

My favourite room is what I have called the “salon” room. It is stark and bright white, clean and simple and quiet. Even the video of the collections playing is silent. Two large reproductions of Balenciaga advertisements feature and one complete wall is papered with a photograph of the Balenciaga salon. Three large photos of two drawings and a model shot of my favourite garment from the show are also featured. The black silk gazar dress, inspired by the abstract paintings of Miró, is perhaps the most “oblique” of the garments in the exhibition and truly shows Balenciaga’s mastery of technique utilising a fabric he had created for him by fabric supplier Abraham. I first saw this dress over twenty years ago at the National Gallery of Victoria and was still startled by its strength and beauty.

The salon room offers a tiny insight into the creative process and just because Balenciaga didn’t speak about his work, doesn’t mean that secrets can’t be teased out. They are there though, in every seam and every ruffle – or marked inside the garments themselves in pencil as with the “Infanta” dress. The garments are his work and his legacy. Perhaps Mr. Bowles does some teasing in the book that accompanies the exhibition. I didn’t buy the book – later to find it was only available from the Institute – so will give him the benefit of the doubt, but based upon the exhibition itself and the lecture he gave, I doubt it. My advice for someone wanting to get into the heart of Balenciaga is to read Lesley Ellis Miller’s Balenciaga, a truly enlightening read. Her observations on the psychological influence of Spain on his work are much more thought provoking than the simple aesthetic associations of Mr. Bowles. Ultimately however what Balenciaga – Spanish Master does is remind us that, despite our desire to pigeonhole and patronise, haute couture can only exist in a world sans frontières. As novelist Celia Bertin wrote in her book Paris a la Mode of the institution of Balenciaga in 1956:

“A religious, vaguely oriental atmosphere permeates the apartment. The customers, young or old, have to adapt themselves to a form of elegance which remains foreign to Parisians, even though it is close to whatever it may be that gives Paris its simplicity and restraint. Balenciaga creates for the Paris scene, and his haute couture for the rest of the world consists of clothes which delight women by robbing them of their national traits.”

Balenciaga – Spanish Master continues through February 19, 2011

Mark Neighbour is the first guest writer we've had one yves & piet, a trend we hope to continue. Mark is a Queensland University of Technology Fashion Studio Lecturer and Technician, QUT Masters Graduate and fashion designer with over 20 years industry experience. His design work and research explores the process of fashion design through the potential that exists between the designer, their material and the processes of making. This means he likes people who can make stuff as well as design it.